Early in my first internship, I recall my mentor back then gave us a good introduction to git, and taught us some useful git commands. From then on, I’ve accumulated my share of learnings from using git over the years, so if you’re just learning git or you’re just entering computer science and would like to learn git: don’t worry, let me share the basic and most useful git commands that I think are good to know~

Note: I’ve been meaning to write this one for a while, but never got to it.

Terminology

To understand how to use git, you need to know the following concepts:

- Remote repository: this is a version of your project that exists on a centralized server like Github. It allows for collaboration on the same project.

- Local repository: the copy of the same project, but on your local machine. You make changes here, and then push your changes to the centralized location (the remote repository), where everyone else can see it.

- Commit: all changes in code are tracked by a history of “commits”. Each commit has a message, by the author (you), detailing what has been changed, as well as the actual code changes made in that commit.

- Branching:

- Each repository has a

main(or master) branch, which contains the source of truth for the repository. Each code change has to be verified through pull request reviews and approvals by other team members, before it is taken into the main branch. - When you do your own development, you can create a new branch that duplicates the state of the main branch, or the current stable code. Then, you make your code changes locally, and create a pull request to merge your branch (with the new code changes) back into the main branch. This ensures that the main branch always has peer-reviewed and production-ready code.

- Each repository has a

- Pull request: Once you are happy with the code changes on your branch, and you’re ready to add it to the current stable code of the

mainbranch, you create a pull request. This makes it clear the changes you have made on Github, and allows you to receive comments from the team on your changes. Once the required reviewers have approved, you can merge your changes into main, and add your changes as a part of the latest and greatest stable code.

SSH keys

To do anything in git, you will need a way to clone the repository, meaning downloading the source code of the project you will be working on from Github onto your local machine. There are different ways of cloning a repository, either through HTTPS or SSH. If you do it through HTTPS, no set up is required, but you will have to enter your github password to authenticate every time you pull/push your changes to the remote repository. Now instead of doing this, most people like to add SSH keys. This is a set of keys that you add to your local machine, which authenticates you to github. That means you won’t have to authenticate on every remote read/write.

The steps are as follows, and documented in the Github docs as well.

- Check if you have any existing keys in the

/.sshdirectory of your laptop, or wsl setup

cd ~/.ssh # change into .ssh dir

ls -la

If you see any file with id_rsa.pub, or id_ed25519.pub, you have an existing key, and you can skip step 2.

- Generate SSH keys

ssh-keygen -t ed25519 -C "<your-email-address>"

Next, you can click enter twice for no password and default location. This will generate a private/public key pair.

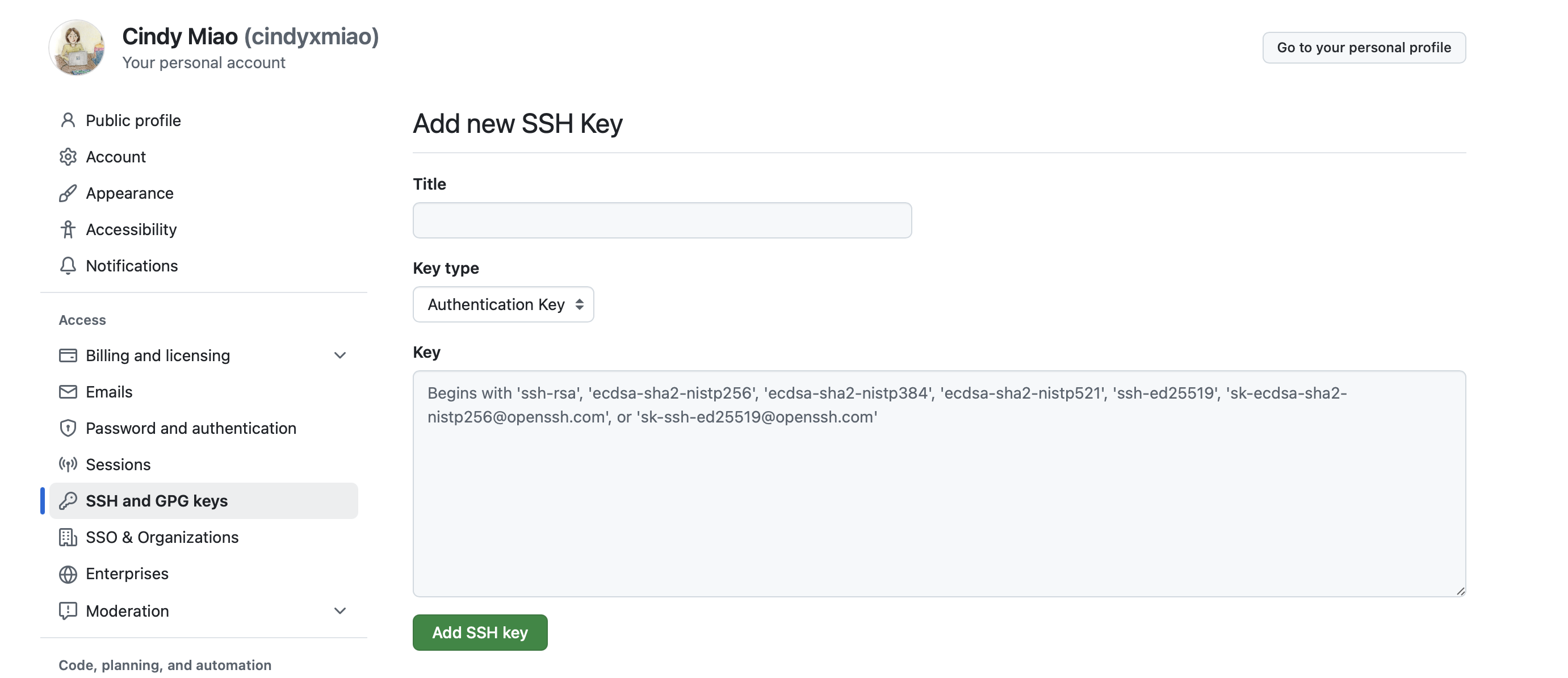

- Add your public key to github

Open your public key file id_ed25519.pub or id_rsa.pub in whatever editor you want, and copy its contents.

Then, paste the contents below, where it says “Key”. Be sure to give your SSH key a Title to, in case you have multiple laptops/environments.

SSH and GPG keys on the left sidebarDone! That was easy, right? Now will you will be able to pull/push to your repositories without having to enter your password every time.

Basic workflow

Suppose your manager asks you to make a bug fix in on of your team’s repositories. You would need to clone the remote respository onto your local computer, make the required bug fix, and then push your changes back up to the remote git repository, such that your team can see it and review your changes before it is merged to the main branch. Here is the regular work flow:

- Clone the damn repo.

git clone <my-repo>

This will clone the remote repository in your current working directory.

- Create a branch.

git checkout -b <my-feature-branch>

Like discussed previously, its best practice to create your own branch, do development work there, and then merge it to main. Unless you are the only author of your project, where in that case you can feel free to work off the main branch.

Make your changes in the source files. Don’t forget to press

control+sto save!Add your changes. There are some different variations of commands you can do here:

- Add all your changes. Might not be good if you want to review your changes, or there’s some files that you don’t want to commit

git add .- Interactively reviews which changes you would like to add to the commit. This is my favorite command, because you can see in the interactive shell exactly which changes you made (and catch it early if you made any typos or mistakes).

git add -u -pWrite your commit message. This should be a descriptive message that details the changes you made in this commit.

git commit -m "this is my first commit! yay!"

- Push your commit to the remote repository.

git push -u origin <my-feature-branch>

You will see that if you don’t add the -u -origin here, you will encounter an error. The next time you push to this branch, you won’t need those tags.

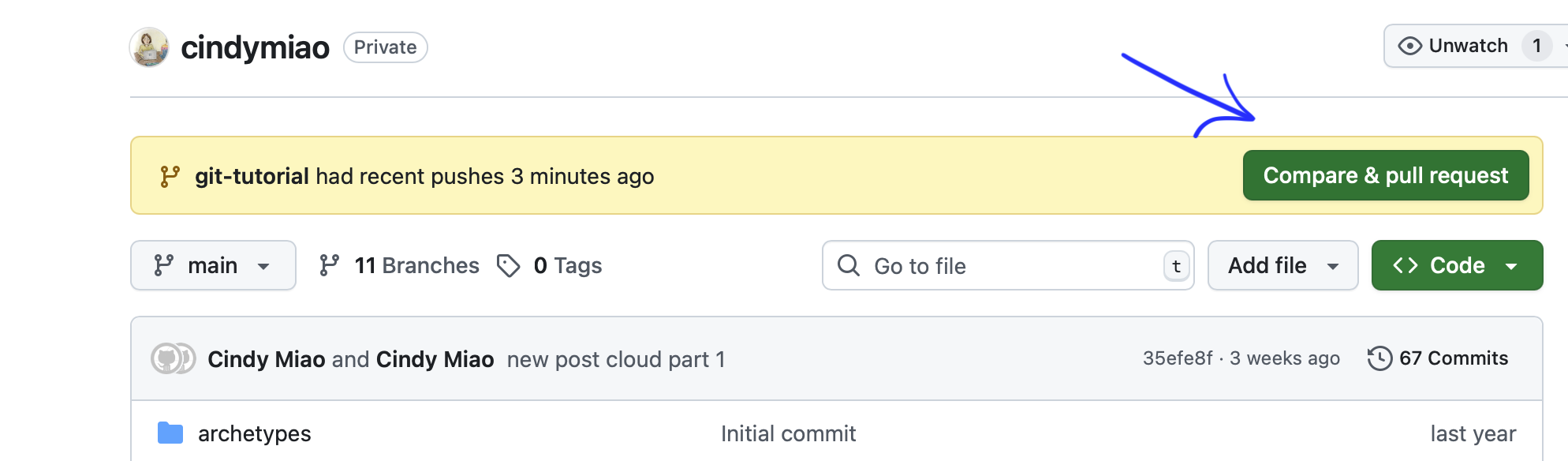

Note that this updates the upstream or remote copy of your branch. However, the main branch still does not have your newest changes. Thus, lastly you will need to:

- Create a pull request to merge your feature branch to main.

Useful git commands

However, sometimes things don’t go to plan, and you need another arsenal of git commands in your belt to fix things. Here are some other cases you might encounter

Editing your last commit

For example, you just committed and pushed something, but realized you made a typo after you looked over your pull request on github. Here’s what you can do without adding a new commit, and letting everyone also see your typo :)

- Make any corrections to your code, and then stage the new changes.

git add .

- Make the new changes on the old commit.

git commit --amend

An interactive shell will pop up such that you can edit the commit message if you wish, otherwise just escape out of the interactive terminal (meaning you agree to the previous commit message)

- Finally, Force push to remote.

git push -f

We have to do a force push on the last step, because we edited the previous commit (basically replaced old commit with new commit), and now our local branch is different from the remote branch, so we have to forcefully update our new commit to the remote (overwriting the old commit).

Obviously, you should not force push on the main/master branch, unless you’re feeling otherwise risky that day. Usually there’s guards preventing you from doing this on company repositories.

Resolving merge conflicts

Now, this is the most tricky one for beginners in my opinion. I remember struggling with this so much in my first computer science class—like what do you mean I have to resolve merge conflicts?? Why are they different and what’s up with the squigglies >>>??

Let’s suppose that you and your friend are working on a project together. You created a branch off of main, and your friend created a branch off of main, at around the same time. Your friend is faster than you, and commits her changes, pushes her branch, and then merges her branch to main.

So when you commit your changes, push to your branch, and make a pull request, it says that what was on the main branch had changed (because your friend had edited it). Now suppose your friend set some variable, m = 5, in her code. And you decided m = 10. Who’s change is the correct one?

Git also cannot figure out who’s change it should take. If you had made a branch after your friend set m = 5, and overwritten it with m = 10, then Git will take your new change. However, because both parties made each change independent of one another (suppose m did not exist in branch main previously), Git doesn’t know who to listen to anymore. That’s when you need to manually resolve the merge conflicts.

You could possibly have a conversation with your partner, and ask why they set m = 5. After the conversation, there are 3 possible outcomes:

- They convince you that

m = 5. So you take their changes (from main), and ignore the incoming changes from your branch - You convince them that

m = 10. So you take your new incoming changes, and ignore the changes on main - For some reason,

m = 5andm = 10should both exist (you are working on a quantum mechanics project involving schrödinger’s cat). Then, you can take both changes.

What does this look like in practice?

Suppose you made some changes in your feature branch <my-feature>, and now you want to merge those changes to main.

- Checkout the main branch.

git checkout main

- Pull any new changes that have occurred on the main branch.

git pull

- Merge your feature branch into main. Note however, if you raise a pull request to merge your feature branch into main, and there are merge conflicts, you will need to merge the otherway around to resolve the conflicts by merging main into your feature branch first, or rather, rebasing your feature branch on top of main (see note below). Then, once the conflicts are resolved, you can finish the pull request and merge your feature branch back into main.

git merge <my-feature>

If there are merge conflicts, meaning that the new changes occurring on the main branch conflicts with your local changes, you will see that git will prompt you to resolve merge conflicts in the local IDE.

- Resolve any merge conflicts.

You can do a quick search in the local IDE for >>>, which indicates places where there are merge conflicts to be resolved. Within the interactive IDE, you can choose whether to:

- take incoming change (from your feature branch)

- take original change (from main)

- or keep both changes

Once you resolve all the lines with >>>, and the code is fully working, you need to commit your changes.

- Make a merge commit.

git add .

git commit

Note that we don’t need to specify a message -m for commit this time, because it will automatically write the commit message for you, something like merging feature into main branch.

- Voilà, you can push the main branch back to remote with the changes from your feature branch merged in.

git push

Note: an alternate to merging is using git rebase <main> on your feature branch, which re-applies the changes from your feature branch on-top of any new changes in main. It is an alternative to merge, without introducing an additional merge conflict.

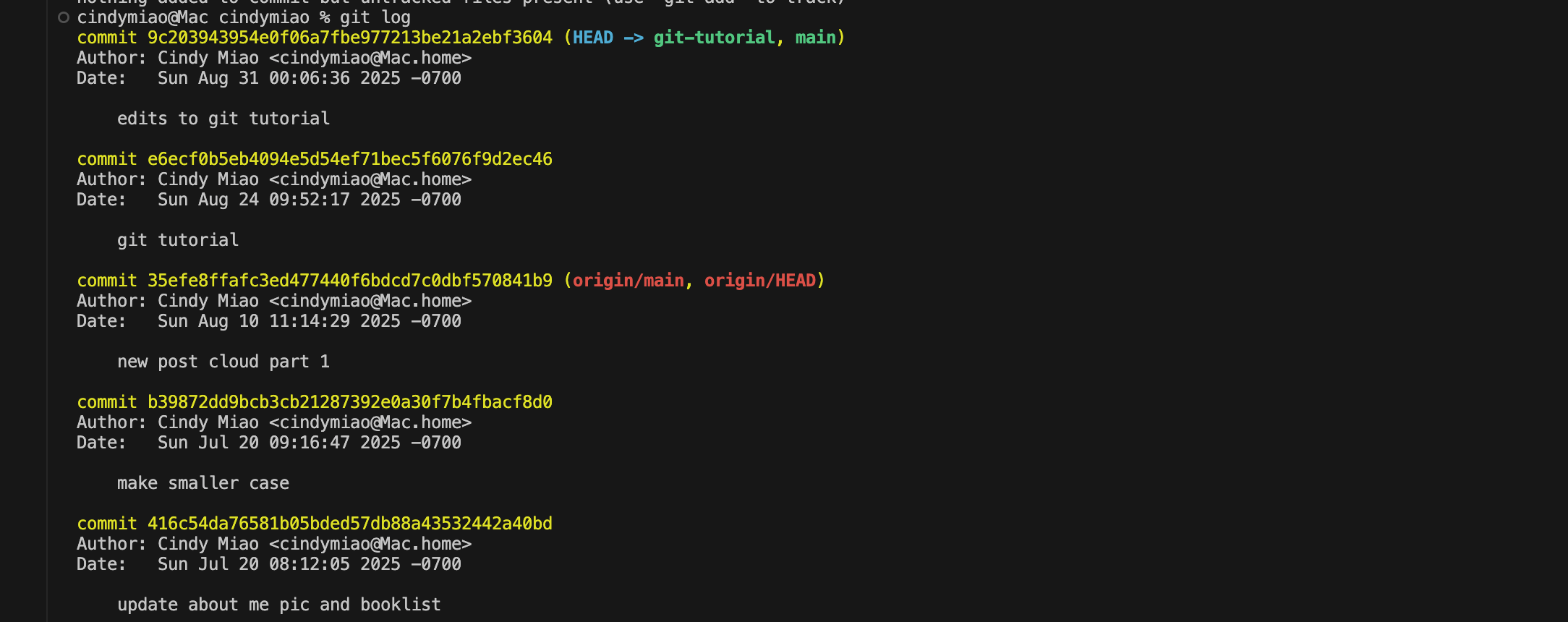

git log

This feels like the ls -la of git (as that is to filesystem). To see the history of the git commits on your current branch just, type the following in your terminal:

From this, we can see that the hash of the last commit was 9c203943954e0f06a7fbe977213be21a2ebf3604, authored by Cindy Miao (that’s me!), with the commit message that I made edits to git tutorial.

Futhermore, we can see that my local branch git-tutorial and main is pointed to this latest commit, whereas my remote main branch is not yet updated and still pointed to 35eTesTtatc3ed471440T6baca7cUabT570841b9.

Similarly, to see what branch you’re currently on, you can do a:

git branch

Re-writing history

This one is a more complex command. Suppose you want to do a git commit --amend, but you want to do it not only on your last commit, but you want to edit all N of the previous commits. Here’s what you can do:

git rebase -i HEAD~N

where N is the number of commits from the current commit that you would like to edit.

Then, Git will show you a list of all the last N commits, and give you the option to add a letter to each of them, depending on what you want to do with that commit.

# Commands:

# p, pick <commit> = use commit

# r, reword <commit> = use commit, but edit the commit message

# e, edit <commit> = use commit, but stop for amending

# s, squash <commit> = use commit, but meld into previous commit

# f, fixup <commit> = like "squash", but discard this commit's log message

# x, exec <command> = run command (the rest of the line) using shell

# b, break = stop here (continue rebase later with 'git rebase --continue')

# d, drop <commit> = remove commit

# l, label <label> = label current HEAD with a name

# t, reset <label> = reset HEAD to a label

# m, merge [-C <commit> | -c <commit>] <label> [# <oneline>]

# . create a merge commit using the original merge commit's

# . message (or the oneline, if no original merge commit was

# . specified). Use -c <commit> to reword the commit message.

#

For example, if you pick edit or “e” for all the past N commits, git will backtrace through history, starting from the last Nth commit. Then, you can edit the last Nth commit, make changes, commit it, and then continue the rebase process, which will allow you to repeat the steps with the last (N - 1)th commit, until the latest commit.

Revert

Okay, suppose you merged a change to <main>, but then realized that you broke something in production…uh oh. Don’t worry, you can just revert that pull request, which will create another commit that reverses the PR. This one is just easy to do on on the IDE (there’s a button on your PR to revert it, after you merge it).

Push your local branch to another remote branch

This one I learned very recently. Suppose you want to overwrite your remote branch with changes from a different local branch. For example, I already have a PR open with the remote branch, but I wanted to completely modify the contents by overwritting it with the commits from another branch, without loosing all the history and comments on that open PR. Then, I can force push the contents of a different local branch to that remote branch (which the PR is open on):

git push -f origin <local-branch>:<remote-branch>

And there you have it, my favorite and most useful git commands! There are plenty others like git stash and git cherry-pick that I didn’t get a chance to cover, but they’re easy to investigate on your own. And last but not least, have lots of fun with version control 😄